John Sherman, American statesman

and author of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Famous Quote

“The few who understand the system will either be so interested in its profits or be so dependent upon its favours that there will be no opposition from that class, while on the other hand, the great body of people, mentally incapable of comprehending the tremendous advantage that capital derives from the system, will bear its burdens without complaint, and perhaps without even suspecting that the system is inimical to their interests.” ― John Sherman

Vital Summary

Biography: John Sherman (1823–1900)

Full Name: John Sherman

Born: May 10, 1823, Lancaster, Ohio, U.S.

Died: October 22, 1900, Washington, D.C., U.S.

Resting Place: Mansfield City Cemetery, Mansfield, Ohio

Political Affiliation: Whig (before 1854), Republican (1854–1900)

Profession: Lawyer, Politician

Nickname: “The Ohio Icicle”

Family Background

Father: Charles Robert Sherman – Justice of the Ohio Supreme Court

Mother: Mary Hoyt Sherman

Siblings: One of 11 children, including notable brothers:

William Tecumseh Sherman – Union General during the Civil War

Charles Taylor Sherman – U.S. District Judge

Hoyt Sherman – Businessman and civic leader

Marriage and Children

Spouse: Cecilia Margaret Stewart (married in 1848)

Children: Adopted daughter, Mary Sherman

Political and Professional Career

U.S. House of Representatives (Ohio’s 13th District): 1855–1861

U.S. Senate (Ohio): 1861–1877, 1881–1897

Secretary of the Treasury: 1877–1881 under President Rutherford B. Hayes

Secretary of State: 1897–1898 under President William McKinley

Legislative Achievements

Sherman Antitrust Act (1890): Principal author of this landmark legislation aimed at curbing monopolies and maintaining market competition.

Financial Reforms: Instrumental in the passage of the National Banking Act and advocated for the gold standard to stabilize the U.S. economy.

Honors and Legacy

Sherman Antitrust Act: Continues to serve as a foundational statute in U.S. antitrust law.

Sherman House Museum: John Sherman Birthplace. His childhood home in Lancaster, Ohio, is preserved as a museum and designated as a National Historic Landmark, located at 137 E Main St, Lancaster, OH 43130

The Evolving Landscape of Economic Power & Regulation

Insights from a Historical Perspective on Market Dynamics, Public Sentiment, and Legislative Response

“The great danger to the public is from the vast accumulation of wealth in the hands of corporations and individuals, which, if permitted, will be a menace to the Republic itself.”

– John Sherman, 1890

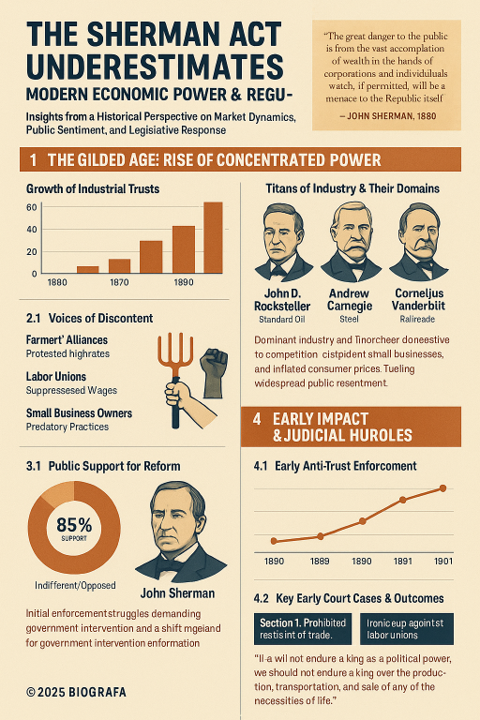

The Gilded Age: Rise of Concentrated Power

The late 19th century, an era of staggering economic expansion, also witnessed the unprecedented accumulation of wealth and power in the hands of a few, leading to the formation of massive industrial trusts that dominated key sectors.

Growth of Industrial Trusts (Illustrative)

This conceptual chart illustrates the perceived rapid increase in the scale and influence of industrial trusts during the late 19th century, leading to significant market concentration.

Titans of Industry & Their Domains

Figures like Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Vanderbilt built vast empires, often through aggressive tactics that stifled competition.

🏭 John D. Rockefeller

Dominated ~90% of oil refining (Standard Oil Trust).

🔩 Andrew Carnegie

Led massive consolidation in the steel industry.

🚂 Cornelius Vanderbilt

Controlled vast railroad networks.

These trusts often led to exorbitant rates for farmers, crushed small businesses, and inflated consumer prices, fueling widespread public resentment.

Public Outcry & The Call for Reform

The unchecked power of monopolies sparked widespread discontent among farmers, laborers, and small business owners, creating a powerful demand for government intervention and a shift from ineffective common law remedies to a federal imperative.

Voices of Discontent

Various segments of society raised their voices against the abuses of concentrated economic power.

- 🌾 Farmers’ Alliances (e.g., Grange): Protested high railroad rates and manipulated commodity prices.

- 🛠️ Labor Unions: Condemned suppressed wages and poor working conditions under powerful corporations.

- 🏪 Small Business Owners: Appealed for protection against predatory practices and market extinction.

- 📰 Muckraking Journalists & Intellectuals: Exposed abuses and fueled public sentiment for reform.

Public Support for Reform (Illustrative)

The growing public outcry created undeniable political pressure for federal action against trusts.

The Sherman Act: A Legislative Landmark

John Sherman’s evolving convictions, moving from favoring regulation to advocating for prohibition of anti-competitive combinations, culminated in the drafting and passage of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 – a pioneering federal effort to curb monopolistic power.

Key Milestones in the Genesis of the Act

Late 1880s

Growing public pressure and recognition of state law inadequacy. Senator Sherman begins drafting federal legislation.

1889-1890

Intense debates and amendments in the House and Senate. Sherman navigates opposition and builds coalitions.

April 8, 1890

The Senate passes the Sherman Anti-Trust Act after months of deliberation.

July 2, 1890

President Benjamin Harrison signs the Sherman Anti-Trust Act into law.

Core Provisions of the Sherman Act (1890)

The Act’s language was deliberately broad to address various forms of anti-competitive behavior.

Section 1: Prohibition of Restraint of Trade

“Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce…is hereby declared to be illegal.”

Section 2: Prohibition of Monopolization

“Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize…any part of the trade or commerce…shall be deemed guilty…”

John Sherman declared, “If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessities of life.”

Early Impact & Judicial Hurdles

The Act’s passage marked a significant step, but its initial impact was tempered by uncertain enforcement and narrow judicial interpretations, highlighting the challenges in translating legislative intent into practical market changes.

Early Anti-Trust Enforcement (Illustrative)

This conceptual chart depicts the perceived initial struggles and inconsistencies in the enforcement of the Sherman Act due to legal challenges and judicial interpretations.

Key Early Court Cases & Outcomes

Initial Supreme Court rulings often limited the Act’s scope.

| Case (Year) | Significance/Outcome |

|---|---|

| United States v. E.C. Knight Co. (1895) | Limited Act’s scope by ruling sugar refining (manufacturing) was not interstate commerce, curtailing ability to break up trusts. |

| Use Against Labor Unions | Ironically, the Act was sometimes applied to labor unions engaging in strikes, deeming them “combinations in restraint of trade.” |

These early challenges meant many trusts continued to operate with little disruption, requiring decades and further legislation to strengthen anti-trust law.

Anti-Trust in the 21st Century: New Frontiers

Over a century later, the Sherman Act remains foundational, yet its application faces new complexities with digital platforms, global markets, and nuanced forms of market dominance that challenge traditional anti-trust frameworks.

Modern Titans & Market Influence

Contemporary giants in tech, retail, and finance present new questions about market power and regulatory response.

📱 Google (Alphabet)

Dominance in search, online advertising, mobile OS.

🛒 Amazon

Vast e-commerce, cloud computing (AWS), logistics.

🛍️ Walmart

Enduring retail dominance, sophisticated supply chain.

💰 BlackRock

Colossal asset manager with investments across nearly all major public companies, raising questions of influence.

These entities often leverage network effects, data accumulation, and strategic acquisitions, complicating traditional anti-trust analysis.

Challenges in Modern Anti-Trust Enforcement (Illustrative)

Regulators face multifaceted challenges in applying century-old laws to rapidly evolving digital and global markets.

Concerns persist about “hidden dominance,” mergers reducing potential competition, and the influence of large corporations on lawmakers and regulators through lobbying and other means, posing ongoing challenges to the spirit of the Sherman Act.

The Enduring Legacy & The Path Forward

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act, born from the Gilded Age’s excesses, remains a vital, though continually tested, cornerstone of American economic policy. Its principles of fair competition and the prevention of undue economic concentration are more relevant than ever in an era of global platforms and digital Goliaths. The “adventure” of ensuring a level playing field, initiated by John Sherman, demands ongoing vigilance, adaptation, and a commitment to balancing innovation with economic justice for all.

The challenge endures: to adapt and apply anti-trust principles effectively to preserve competition and protect the public interest in the face of ever-evolving corporate strategies.